Youngsters will not remember this ……… but there was a time when humanity had to actually get off the sofa and walk to the TV to change the channel. There was a time when all food had to be prepared and cooked from scratch, and the notion of having a mini-nuclear reactor in the kitchen heating your ready-made meal seemed preposterous. There was a time when mobile phones only allowed you to make calls, not access the sum of all human knowledge (and cat memes) from anywhere in the world.

Society wants everything faster, easier and more painless, so like them or loathe them, modern conveniences are here to stay. Aiming for a world with more simplistic processes (which has ironically resulted in a level of technological complexity our ancestors never had to deal with) has gone completely hand in hand with the digital revolution, and already resulted in the almost complete eradication of all things analogue. Mechanical systems look set to be the next victims, with direct human control slowly being passed to digital systems which can react faster, don’t get tired and don’t make mistakes. And never complain.

The automotive world has not been oblivious to these developments. Simple things such as window winders were long ago replaced by electric windows. The same for mirrors, sunroofs and anything else which required physical exertion. And slowly but surely, these changes have started to trickle into the mechanics of the cars themselves, affecting how your car actually drives. Power-steering adds a layer of hydraulic (or electric) assistance to augment the effort of actually turning your front wheels. ABS uses sensors to detect if the wheels lock up under braking, and then activates hydraulic valves to limit or interrupt the braking forces going to those wheels – allowing you to maintain some element of directional control. And so on.

The automotive world has not been oblivious to these developments. Simple things such as window winders were long ago replaced by electric windows. The same for mirrors, sunroofs and anything else which required physical exertion. And slowly but surely, these changes have started to trickle into the mechanics of the cars themselves, affecting how your car actually drives. Power-steering adds a layer of hydraulic (or electric) assistance to augment the effort of actually turning your front wheels. ABS uses sensors to detect if the wheels lock up under braking, and then activates hydraulic valves to limit or interrupt the braking forces going to those wheels – allowing you to maintain some element of directional control. And so on.

The humble manual gearbox has not been immune to progress either. Used widely in all types of cars for many decades now (along with trucks and other vehicles), it has long been the conventional choice of gearbox for most drivers – well, in Europe at least. In the USA, 29% of cars were sold with manual gearboxes in 1987. By 2003 that had dwindled down to 8.2%, and by 2011 it was at 3.8%. By comparison, it is estimated that in 2003 only around 15% of new cars sold in Europe came with an auto-box. By 2011 that figure had risen to around 30%, but manual still remains the most popular choice for European drivers.

So, why the clear disparity? There are many reasons, but the most likely one seems to be simple : size matters. American infrastructure and road networks evolved in a drastically different way to Europe, and this resulted in American cars being much larger and weightier than their European and Japanese counterparts – a trait which they still possess to this day. In post-war Europe, the cars that sold in the greatest numbers were all relatively small and lightweight models – the VW Beetle, the Fiat 500, the Citroen 2CV, the Austin Mini. Nudged along by strict taxation, this encouraged European manufacturers to develop small engines – usually less than 1 litre in size and often producing well under 60bhp. This contrasted vividly with the USA’s use of large capacity engines, often upwards of 3 litres and multiple cylinder configurations. The low weight and power of European cars thus meant that they were often unsuitable for the type of heavy torque convertor automatic boxes which were favoured by Americans at the time, with the manual box quickly becoming the more preferred option due to its simpler and lighter installation. Add to that the fact that two US automotive giants (GM and Chrysler) were among the first mass developers of auto boxes worldwide in the 1930s, thereby gaining a large foothold in their domestic market. Car production has now moved on to the point where any gearbox can be mated to virtually any engine with no major restrictions, but it seems the seeds sown in those early days meant that the manual never really stood a chance in the USA when it came to large volume car sales.

We have learnt over the years though, that what is popular in large volumes is not always popular in the niche sectors. In the early days of sports cars and other high performance vehicles, both consumers and the development teams behind the vehicles quickly cottoned on to the benefits of having a manual gearbox. Performance cars weren’t purchased just to get from A-B like the vast majority of their slower siblings; they were purchased because their new owners enjoyed spirited driving, even though they were usually more expensive, less comfortable, harder to maintain and often temperamental. It was a brazen case of heart over head, with owners pursuing – as Evo magazine succinctly puts it – ‘the thrill of driving’.

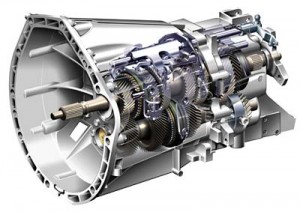

The manual gearbox married itself to this ethos perfectly. It offered a level of engagement with the car and engine which could never be replicated by an auto ‘box, providing an increased level of control for any driver in a performance vehicle who needed their reactions to be swift, precise and unsullied by any weak links between their inputs and the car’s behaviour. Not only that, but the tactility awarded by the physical sensation of feeling the gearbox cogs (‘dogs’) engage on a smooth manual ‘box made for a sensory experience which was totally absent when using an auto.

Hence – for a long time – the manual gearbox became almost synonymous with performance cars. Manufacturers capitalised on this and focused some of their energies on progressing continuous development of the manual, using positive PR and successful results from their motorsport divisions to continue pushing for increased efficiency and economy. The 3-speed ‘box (generally used throughout Europe until the 1950s) gave way to the 4-speed, as used in the Jaguar E-Type, amongst others. After many years of loyal service however, the 4-speed had fallen into almost total disuse by the end of the 1980s, with virtually all major manufacturers opting to go with 5-speed ‘boxes. These in turn were naturally succeeded by the 6-speed box, offering further benefits to economy, refinement and flexibility. And as of 2015, Porsche and Chevrolet are but 2 manufacturers who are now deploying 7-speed manuals in some of their performance vehicles – such as the latest 911 and Corvette.

Hence – for a long time – the manual gearbox became almost synonymous with performance cars. Manufacturers capitalised on this and focused some of their energies on progressing continuous development of the manual, using positive PR and successful results from their motorsport divisions to continue pushing for increased efficiency and economy. The 3-speed ‘box (generally used throughout Europe until the 1950s) gave way to the 4-speed, as used in the Jaguar E-Type, amongst others. After many years of loyal service however, the 4-speed had fallen into almost total disuse by the end of the 1980s, with virtually all major manufacturers opting to go with 5-speed ‘boxes. These in turn were naturally succeeded by the 6-speed box, offering further benefits to economy, refinement and flexibility. And as of 2015, Porsche and Chevrolet are but 2 manufacturers who are now deploying 7-speed manuals in some of their performance vehicles – such as the latest 911 and Corvette.

Whilst the majority of manual cars employ a very similar installation model for the gearbox (typically a ‘H-pattern’ shift, with the gearstick protruding from the main transmission tunnel which runs along the centre of the car and under the dashboard), there have been variations over the years.

The ‘Dog-leg’ pattern saw manufacturers re-jig the gear layout; First gear was moved to the bottom left position (where it would typically be at the top left), second up-and-right, third below, and so on. This pattern was primarily used in race cars, and road cars inspired by race models – such as the iconic BMW E30 M3. The Dog-leg gearbox was developed as a direct response to suggestions from race drivers that it would be more desirable to have second and third gear directly above/below each other, as that particular gear change occurs much more frequently in racing than first to second. Although successful amongst racers, the unconventional pattern was not popular amongst non-racers accustomed to the traditional H-pattern, and thus was never deployed on a mass production basis.

The column-mounted gearstick was another variation on the usual model, and one which you have most likely seen on American models. Here, the gearstick itself is mounted on the steering column of the car, often accompanied by a gear selection indicator adjacent to it. The main advantage to this technique was the ability to change gear whilst still holding the steering wheel, but the extra space freed up by the lack of a typical transmission-tunnel gearstick was an additional benefit. However, this installation did require a more complicated gear linkage assembly.

The console mounted gearstick achieved a kind of middle-ground between the usual floor-mounted style, and the column-mount. Here, the gearstick is typically mounted near the bottom of the vehicle’s instrument panel. Like the column-mount gearstick, it frees up valuable floor space but does so without a need for any complicated gear linkage – it remains mounted to the car’s transmission in much the same way as a floor-mount. Many fans of this style praise the dexterity offered, with the gearstick’s adjacency to the steering wheel allowing for smoother and faster accessibility. Many cars utilise this type of installation nowadays, but amongst performance car fans the EP3 Honda Civic Type R is probably the most notable recent example of such.

Transitions from old technology to new – in any walk of life – rarely occur overnight. Whilst the manual gearbox was still enjoying immense popularity, manufacturers were already working on the next stages of development – which began to remove certain levels of human control and move towards a future where the mechanical part of the gearbox was augmented by digital systems. The Semi-Manual gearbox (such as BMW’s SMG (Sequential Manual Gearbox) and Alfa Romeo’s Selespeed) was an early example of such; also known as the ElectroHydraulic Manual, it was essentially a conventional manual gearbox in design, but one where the control mechanism was entirely computerised. There was no clutch pedal; drivers were able to select gear by using paddles located behind the steering wheels, or simply by tapping the sequential-manual gearstick forward or back. Doing so activated a servo which engaged the clutch when necessary. This type of gearbox provided many benefits; more longevity (as with nearly all modern post-manual gearboxes, it is virtually impossible to ‘crunch’ a gear or select the wrong gear  at high RPM), potentially smoother gearchanges, and electronically assisted features such as hill-start assist and launch control. The electronic systems also allowed for some degree of versatility; numerous shift speeds could be set (with the software automatically applying varying degrees of clutch slippage) from slow to very fast, albeit with a proportional reduction in fluidity. Despite the name which suggests it is the bastard offspring of two mismatched parents, the semi-manual arguably inherits the best traits of both – an auto mode allowing for relaxed town driving, and a manual mode for those occasions where the driver wants more involvement. The fact that BMW released one of their most sought-after flagship performance models – the E46 M3 CSL – with only an SMG option, spoke volumes about their confidence in this type of gearbox.

at high RPM), potentially smoother gearchanges, and electronically assisted features such as hill-start assist and launch control. The electronic systems also allowed for some degree of versatility; numerous shift speeds could be set (with the software automatically applying varying degrees of clutch slippage) from slow to very fast, albeit with a proportional reduction in fluidity. Despite the name which suggests it is the bastard offspring of two mismatched parents, the semi-manual arguably inherits the best traits of both – an auto mode allowing for relaxed town driving, and a manual mode for those occasions where the driver wants more involvement. The fact that BMW released one of their most sought-after flagship performance models – the E46 M3 CSL – with only an SMG option, spoke volumes about their confidence in this type of gearbox.

Rather than automating a manual gearbox, some manufacturers took the opposite approach – and sought instead to introduce more manual control to auto ‘boxes. Porsche were advocates of this concept, and developed a new type of gearbox called Tiptronic, which was added to many of their models from the early 90s onwards. Using numerous sensors to monitor throttle position and movement, engine and road speed, ABS activation, and fuel-delivery, the automatic box adapted to a driver’s particular style by choosing among five available shift modes, all controlled by software. Crucially though, there was an override facility – accessed by pushing the gearlever to the side and then up/down – which allowed the driver to manually control the shift mode and essentially change up and down through the limited automatic gears. Later versions of Tiptronic had buttons on the steering wheels which provided the same function; these were essentially the (unpopular) predecessors of the paddle shift.

The sequential-manual was a step towards the future for many manufacturers, but it was still very much compromised by its inherently manual DNA, which limited how quickly and how smoothly it could shift gears. Similarly, the Tiptronic-style ‘box was always going to be restricted by its automatic underpinnings, which meant it lacked precision and couldn’t consistently judge upshifts and downshifts. The next major evolution of the gearbox attempted to address this. Known as the Dual-Clutch Transmission (DCT), this gearbox took a novel approach to maximising efficiency : as its name suggests, it utilised not one, but two clutches. One of the fundamental constraints of manual gearboxes, and also Semi-Manuals, was that the use of a single clutch meant there was an on-off power delivery between gearchanges as the clutch disengaged the engine from the gearbox, interrupting the power flow to the transmission. As all drivers will know, this constraint often manifests itself as a noticeable thump/jerk when changing gear abruptly. DCT’s use of two clutches, totally independent of each other and controlled by sophisticated electronics and hydraulics, countered this effect. One clutch engages odd gears, and the other engages the even gears – by doing so, there is never any interruption of power to the engine and gearchanges are carried out – for the most part – seamlessly. Possessing all the benefits of the Sequential-Manual and more, DCT also brings one more major advantage to the table – improved economy, as a direct result of eliminating the engagement/disengagement normally required with a single-clutch transmission.

Most car manufacturers now have their own version of DCT, but the first mass-production version was released by Volkswagen in the early 2000s and was called DSG – Direct Shift Gearbox. Also employed by Audi for many of its models (under the label ‘S-Tronic‘), it has been resoundingly popular amongst VAG consumers. Constant revisions and updates over the years (both to the mechanical technology and also the electronic systems governing it) have meant that the very latest versions of DSG fitted to some of VAG’s performance models can change gear in as little as 8ms. Contrast this with the shift times attributed to a typical manual driver, which generally average between 500ms and 1s. The adaptable and scalable nature of DSG gearboxes also mean that they can be fitted to mass-produced bread and butter models such as the Golf TDi, or to limited production supercars like the Bugatti Veyron.

DCT has also been adopted by many other notable manufacturers, all adding their own touches to the original vision. BMW have moved on from SMG I &  II, and now use a 7-speed DCT setup for some of their more powerful and performance models such as the 135i, M4 and M5. Nissan too have opted to side with a 6-speed dual-clutch transmission for their mighty R35 GTR, whilst Porsche have long moved on from Tiptronic and christened their dual-clutch offering as ‘PDK‘ – Porsche Doppelkupplung. However, one of the biggest proponents of DCT technology (and transmission development on a whole) has been Ferrari. With their major investment in F1’s cutting edge tech, and that know-how eventually seeping down into their road cars, they have long been lauded as having some of the most precise and fastest-reacting gearboxes in the world. When it comes to technology, it is often Ferrari who lead the game for all other manufacturers, so it is a telling sign that virtually all their most recent models – including the California, 458 and FF – come with a dual-clutch ‘box as standard. Indeed, not a single example of their well-received 599 was sold in manual form in the UK. Despite automotive journalists and critics alike bemoaning the loss of the iconic Ferrari open-gate shifter, it appears that consumers and their cheque books do not have the same concern.

II, and now use a 7-speed DCT setup for some of their more powerful and performance models such as the 135i, M4 and M5. Nissan too have opted to side with a 6-speed dual-clutch transmission for their mighty R35 GTR, whilst Porsche have long moved on from Tiptronic and christened their dual-clutch offering as ‘PDK‘ – Porsche Doppelkupplung. However, one of the biggest proponents of DCT technology (and transmission development on a whole) has been Ferrari. With their major investment in F1’s cutting edge tech, and that know-how eventually seeping down into their road cars, they have long been lauded as having some of the most precise and fastest-reacting gearboxes in the world. When it comes to technology, it is often Ferrari who lead the game for all other manufacturers, so it is a telling sign that virtually all their most recent models – including the California, 458 and FF – come with a dual-clutch ‘box as standard. Indeed, not a single example of their well-received 599 was sold in manual form in the UK. Despite automotive journalists and critics alike bemoaning the loss of the iconic Ferrari open-gate shifter, it appears that consumers and their cheque books do not have the same concern.

And so the manual gearbox finds itself entering 2015, healthy and fighting fit perhaps, but nonetheless looking a little long in the tooth and no longer able to keep up with younger competitors. Will there still be a role for the manual gearbox in 2020? 2025? 2040? The trend seems to suggest that may not be the case unfortunately. With dual clutch transmissions offering superior economy, smoother gearchanges, more flexibility, reduced weight and greater reliability, the manual’s days seem to be numbered. It is also easier for most manufacturers to integrate DCT boxes than manual variants with all the electronic systems of modern sports cars, such as ESP, traction control, e-diffs, and so on. Whilst the DCT gearbox was once the expensive and exclusive preserve of top-end performance and niche models, it’s presence is now starting to be felt amongst the masses also. VW’s contribution has already been mentioned; Renault, Vauxhall and Jaguar too are introducing dual-clutch technology to their mass production models. And it’s increasingly likely that all car manufacturers will eventually follow suit.

“There’s still a market out there for certain performance models which will be sold to purists and those who lust after a manual shift though, right?”, I hear you cry. Perhaps not. Engine technology has also moved on somewhat from yesteryear. In this burgeoning age of advanced hybrids and electric cars which can react almost instantaneously to driver inputs, the manual gearbox seems a little, well …………… agricultural. Some might even say primitive. After all, who buys a new blu-ray drive for watching films in glorious high-definition, and then does so through an old monochrome television? In the same way, it’s difficult to imagine an advanced hybrid engine utilising anything less than a computer-controlled DCT ‘box which can help extract the maximum potential from that engine. Manufacturers promoting their newest supercars and hypercars have no desire to diminish their insane performance figures by inserting a gearbox which (arguably) can’t keep up with the engine. The car market is obviously not just limited to hypercars and supercars, but when even the Fords and Vauxhalls of this world seem to be phasing DCT into all their models, we have to stare the truth in the face : the manual gearbox simply doesn’t make much sense to them anymore.

The manual gearbox has never really made much sense at all though. At least 71% of Americans probably realised this some time ago – why  change manually at all, when a good automatic box will do it all for you? And on paper, DCT just about trumps it in every way. The appeal of the manual ‘box has never been one which can be explained logically on paper though; it’s an emotive, subjective topic, all about tactility and sensation and that feeling of having complete control over your car – man and machine mutually engaged – without any computer system interjecting with 1’s and 0’s. It’s an appeal which only a minority of us can understand, we performance car fans, and which those who use a car purely to get from point to point will never fathom.

change manually at all, when a good automatic box will do it all for you? And on paper, DCT just about trumps it in every way. The appeal of the manual ‘box has never been one which can be explained logically on paper though; it’s an emotive, subjective topic, all about tactility and sensation and that feeling of having complete control over your car – man and machine mutually engaged – without any computer system interjecting with 1’s and 0’s. It’s an appeal which only a minority of us can understand, we performance car fans, and which those who use a car purely to get from point to point will never fathom.

Whilst it may be slightly depressing to imagine a future where learner drivers will only ever learn to change gear by flicking a paddle behind the steering wheel (which raises another question – will drivers schooled only with paddle shifters be legally allowed to drive a manual?), we can at least take solace in the fact that there is still a rich market of used manual performance cars out there which will fast become classics over the next 20-30 years, and which will remain the antithesis to the silent, zero-emission and likely gear-free electric cars we’ll all be driving in 2040.

It’s a small consolation ………………… but infinitely preferable to having to go to a car museum to once again see our old friend, the H-pattern gearstick.